- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

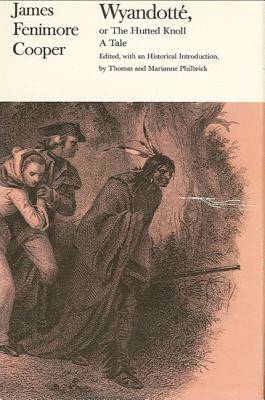

"One of the misfortunes of a nation, is to hear little besides its own praises," wrote James Fenimore Cooper in his Preface to Wyandotté in 1843. The novel arrived at a time when a patriotic mythology about the American Revolution was developing, and Cooper's somber tale of the sufferings of an isolated family in upstate New York during the Revolution was not congruent with the celebratory stories then being told. One reviewer indeed objected to Cooper's "cynicism which hunts after cracks and crevices and unshapely stones in the altar of our political devotion."

In its critical trenchancy, somber tone, and subdued action, Wyandotté is representative of the strongest novels of Cooper's last decade. The elements of romance that are prominent in his fiction of the 1820s here give way to a new emphasis upon characterization and a new interest in familial life. As Edgar Allen Poe observed, in Maud Meredith Cooper creates his most spirited heroine, and in Saucy Nick, his most credible Indian.

"Nothing is truly patriotic," Cooper warns us in his Preface, "that is not strictly true and just." In his last tale of the Revolution, he leaves national self-congratulation to the orators and newspaper editors and hews to his own demanding conception of devotion to his country.

In its critical trenchancy, somber tone, and subdued action, Wyandotté is representative of the strongest novels of Cooper's last decade. The elements of romance that are prominent in his fiction of the 1820s here give way to a new emphasis upon characterization and a new interest in familial life. As Edgar Allen Poe observed, in Maud Meredith Cooper creates his most spirited heroine, and in Saucy Nick, his most credible Indian.

"Nothing is truly patriotic," Cooper warns us in his Preface, "that is not strictly true and just." In his last tale of the Revolution, he leaves national self-congratulation to the orators and newspaper editors and hews to his own demanding conception of devotion to his country.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 434

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780873954143

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 30/06/1981

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Gewicht:

- 752 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 302 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.