Bedankt voor het vertrouwen het afgelopen jaar! Om jou te bedanken bieden we GRATIS verzending aan op alles gedurende de hele maand januari.

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Bedankt voor het vertrouwen het afgelopen jaar! Om jou te bedanken bieden we GRATIS verzending aan op alles gedurende de hele maand januari.

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

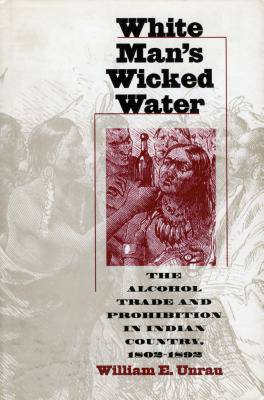

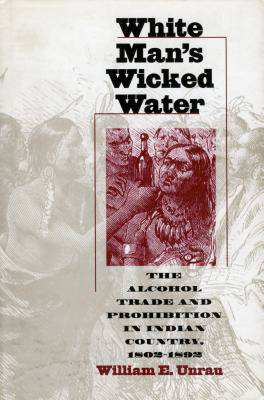

White Man's Wicked Water

The Alcohol Trade and Prohibition in Indian Country, 1802-1892

William E Unrau

Hardcover | Engels

€ 42,45

+ 84 punten

Uitvoering

Omschrijving

"The inordinate indulgence of Indians in spiritous liquors is one of the most deplorable consequences which has resulted from their intercourse with civilized man."--Governor Lewis Cass, Michigan Territory, 1827 "Often I have been compelled to ask myself, 'Who is the civilized and who is the savage?' Their principal vices are emphatically our vices. If they get drunk it is upon our whiskey. . . . [A]nd yet we claim to be 'civilized' and freely deal out to them the epithet 'savage.'"--The Reverend William H. Goode, reflecting on his early 19th-century sojourn in Indian Country In White Man's Wicked Water, Unrau tells the compelling story of how an alcohol-sodden society introduced drink to the Indians. That same society then instituted futile policies to control the flow of alcohol to tribes who, as one superintendent put it, "have not the moral force to resist temptation." Unrau dispels that racial-deficiency theory and debunks the belief that prohibition was carried out by well-intended reformers. Unrau shows that, contrary to the perniciously false image of the innately "depraved savage," Indians actually learned their "uncivil" behavior by emulating--in hopes of accommodating--"civilized" men. Indian inebriation in the nineteenth century, he shows, essentially mimicked the habits of white Americans who-spurred on by prevailing attitudes and federal law-were aspiring to integrate the natives into the cultural mainstream. Prohibition zealots, intent upon soothing white anxieties, were far more concerned with this goal than with stemming the flow of alcohol. Scholars have often viewed the sale of alcohol to Native Americans as a ploy by Euro-Americans to trick them into unfair land and trade deals. But Unrau makes it clear that alcoholic consumption by Native Americans was the inevitable consequence of cultural confluence, not of conscious white subversion. To support his arguments, Unrau has closely examined previously neglected records pertaining to illicit alcohol trafficking, its tie to the land-cession/annuity-distribution system, and the influence of federal subsidy to non-Indian, western development. From these sources, he provides surprising new insights into alcohol use and abuse in relation to Indian removal. Unrau also sheds new light on nineteenth-century prohibition attempts in the trans-Missouri West (primarily Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma) up to the absolutist prohibition law of 1892.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 192

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780700607792

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 28/06/1996

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 157 mm x 235 mm

- Gewicht:

- 512 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 84 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.