Door een staking bij bpost kan je online bestelling op dit moment iets langer onderweg zijn dan voorzien. Dringend iets nodig? Onze winkels ontvangen jou met open armen!

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Door een staking bij bpost kan je online bestelling op dit moment iets langer onderweg zijn dan voorzien. Dringend iets nodig? Onze winkels ontvangen jou met open armen!

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

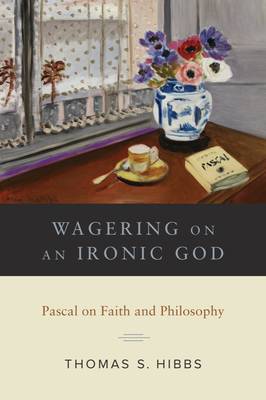

€ 65,95

+ 131 punten

Omschrijving

"Philosophers startle ordinary people. Christians astonish the philosophers."

--Pascal, Pensées

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 216

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781481306386

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/03/2017

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 155 mm x 231 mm

- Gewicht:

- 480 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 131 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.