Wil je zeker zijn dat je cadeautjes op tijd onder de kerstboom liggen? Onze winkels ontvangen jou met open armen. Nu met extra openingsuren op zondag!

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Wil je zeker zijn dat je cadeautjes op tijd onder de kerstboom liggen? Onze winkels ontvangen jou met open armen. Nu met extra openingsuren op zondag!

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

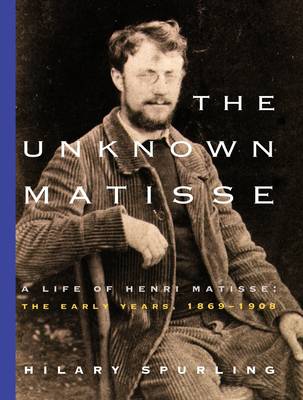

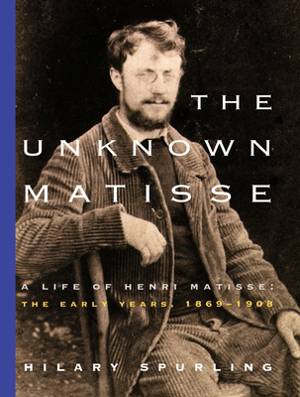

The Unknown Matisse

A Life of Henri Matisse: The Early Years, 1869-1908

Hilary Spurling

Paperback | Engels

€ 52,45

+ 104 punten

Uitvoering

Omschrijving

Henri Matisse is one of the masters of twentieth-century art and a household word to millions of people who find joy and meaning in his light-filled, colorful images--yet, despite all the books devoted to his work, the man himself has remained a mystery. Now, in the hands of the superb biographer Hilary Spurling, the unknown Matisse becomes visible at last. Matisse was born into a family of shopkeepers in 1869, in a gloomy textile town in the north of France. His environment was brightened only by the sumptuous fabrics produced by the local weavers--magnificent brocades and silks that offered Matisse his first vision of light and color, and which later became a familiar motif in his paintings. He did not find his artistic vocation until after leaving school, when he struggled for years with his father, who wanted him to take over the family seed-store. Escaping to Paris, where he was scorned by the French art establishment, Matisse lived for fifteen years in great poverty--an ordeal he shared with other young artists and with Camille Joblaud, the mother of his daughter, Marguerite. But Matisse never gave up. Painting by painting, he struggled toward the revelation that beckoned to him, learning about color, light, and form from such mentors as Signac, Pissarro, and the Australian painter John Peter Russell, who ruled his own art colony on an island off the coast of Brittany. In 1898, after a dramatic parting from Joblaud, Matisse met and married Amélie Parayre, who became his staunchest ally. She and their two sons, Jean and Pierre, formed with Marguerite his indispensable intimate circle. From the first day of his wedding trip to Ajaccio in Corsica, Matisse realized that he had found his spiritual home: the south, with its heat, color, and clear light. For years he worked unceasingly toward the style by which we know him now. But in 1902, just as he was on the point of achieving his goals as a painter, he suddenly left Paris with his family for the hometown he detested, and returned to the somber, muted palette he had so recently discarded. Why did this happen? Art historians have called this regression Matisse's "dark period," but none have ever guessed the reason for it. What Hilary Spurling has uncovered is nothing less than the involvement of Matisse's in-laws, the Parayres, in a monumental scandal which threatened to topple the banking system and government of France. The authorities, reeling from the divisive Dreyfus case, smoothed over the so-called Humbert Affair, and did it so well that the story of this twenty-year scam--and the humiliation and ruin its climax brought down on the unsuspecting Matisse and his family--have been erased from memory until now. It took many months for Matisse to come to terms with this disgrace, and nearly as long to return to the bold course he had been pursuing before the interruption. What lay ahead were the summers in St-Tropez and Collioure; the outpouring of "Fauve" paintings; Matisse's experiments with sculpture; and the beginnings of acceptance by dealers and collectors, which, by 1908, put his life on a more secure footing. Hilary Spurling's discovery of the Humbert Affair and its effects on Matisse's health and work is an extraordinary revelation, but it is only one aspect of her achievement. She enters into Matisse's struggle for expression and his tenacious progress from his northern origins to the life-giving light of the Mediterranean with rare sensitivity. She brings to her task an astonishing breadth of knowledge about his family, about fin-de-siècle Paris, the conventional Salon painters who shut their doors on him, his artistic comrades, his early patrons, and his incipient rivalry with Picasso. In Hilary Spurling, Matisse has found a biographer with a detective's ability to unearth crucial facts, the narrative power of a novelist, and profound empathy for her subject.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 512

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780375711336

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 18/10/2005

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 179 mm x 235 mm

- Gewicht:

- 929 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 104 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.