Bedankt voor het vertrouwen het afgelopen jaar! Om jou te bedanken bieden we GRATIS verzending (in België) aan op alles gedurende de hele maand januari.

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- In januari gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Bedankt voor het vertrouwen het afgelopen jaar! Om jou te bedanken bieden we GRATIS verzending (in België) aan op alles gedurende de hele maand januari.

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- In januari gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

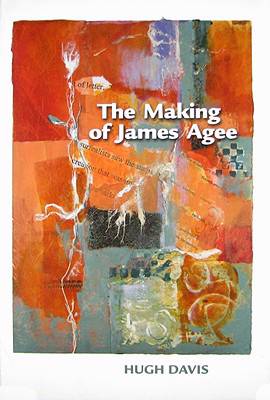

Wildly productive during his short life, James Agee (1909-1955) is today perhaps best remembered as a novelist, but he was also a poet, screenwriter, journalist, essayist, book reviewer, and movie critic. In this volume, Hugh Davis takes a comprehensive look at Agee's career, showing the interrelatedness of his concerns as a writer.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 296

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781572336070

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/07/2008

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Gewicht:

- 456 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 127 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.