- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

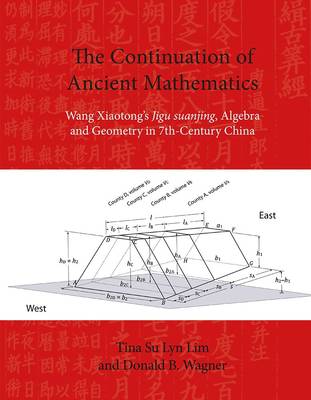

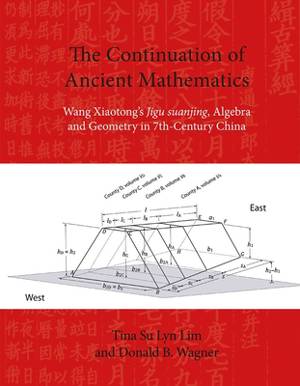

The Continuation of Ancient Mathematics

Wang Xiaotong's Jigu Suanjing, Algebra and Geometry in 7th-Century China

Tina Su Lyn Lim, Donald B WagnerOmschrijving

After the collapse of Roman civilization, knowledge of mathematics dwindled in Europe. In the Arab world, however, the works of ancient mathematicians like Euclid were preserved and built upon by new thinkers like al-Khwarizmi, who became instrumental in spreading Indian mathematics and numerals to the West. What is little known by Western historians, however, is that a parallel development of mathematical knowledge was happening in China during the same period. A rare glimpse of this world is offered via a translation and elaboration of one of the canons of classical Chinese mathematical education. Wang Xiaotong's Jigu suanjing (or Continuation of ancient mathematics) shows us a stage in the development of the Chinese traditional algebra of polynomials from the 1st to the 14th century CE. Here in the 7th century, columns of numbers used in root extraction procedures are recognized as equations that can be solved numerically, but these equations cannot yet be manipulated. Wang Xiaotong arrives at numerically solvable polynomials through a variety of ad hoc techniques, including geometric constructions and rhetorical algebra. In the 18th century, it would be shown that all of his problems could be solved by straightforward algebraic manipulation of polynomials using 14th-century Chinese methods. Lim and Wagner's in-depth study of the Continuation brings this work to an international audience unfamiliar with the history and particulars of Chinese mathematical knowledge. Their worked examples also illuminate the text and invite comparison with the work of medieval mathematicians in the Middle East and Europe.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 232

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9788776942175

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/06/2017

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 213 mm x 267 mm

- Gewicht:

- 566 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.