- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

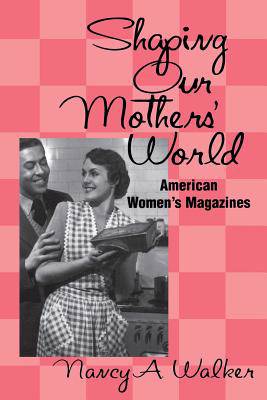

How midcentury periodicals that fostered an indelible middle-class ideal for American women also confronted the happy homemaker stereotype Read by millions of women each month, such mainstream periodicals as Ladies' Home Journal and McCall's delivered powerful messages about women's roles and behavior. In 1963 Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique accused the genre of helping to create what Friedan termed "the problem that has no name" -- that is, presenting women as stereotypical happy homemakers with limited interests and abilities. But this ideal of contented, domestic women was far from monolithic in the periodical literature of the time. Nancy A. Walker's analysis of a wide range of magazines, including Good Housekeeping, Vogue, Mademoiselle, Redbook, and others, reveals their depiction of a broader, fuller image of womanhood. As she notes a reflection of complex debates about the nature of domestic life in the 1940s and 1950s, she perceives editorial policies that mixed the banalities with urgent actualities. Rather than making isolated decisions about content, editors interacted with advertising agencies, with manufacturers of products, with experts in such fields as nutrition, medicine, technology, and childcare, and with the preferences and values of their readers. When World War II altered family patterns by taking millions into the armed services and drawing many women to jobs in defense plants, magazine articles both supported and attacked the new roles women took, while applauding women's home-front contributions to the war effort. After the war the magazines reflected Cold War anxieties while touting the rising consumer culture. Even as magazine ads promoted a white, suburban, middle-class ideal, such series as "How America Lives" in Ladies' Home Journal revealed a society that was economically and ethnically diverse. The pages of women's magazines of the 1940s and 1950s helped to shape and expand the domestic world our mothers inhabited. Examining the articles, fiction, advice columns, and advertisements that the magazines comprised during midcentury, Walker argues persuasively that the contradictory messages were a reflection of complex cultural values and institutions at a time when the domestic world became increasingly important as both a symbol of American democracy and the site of personal fulfillment.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 276

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781578062959

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 2/04/2013

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 150 mm x 230 mm

- Gewicht:

- 408 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 77 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.