- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

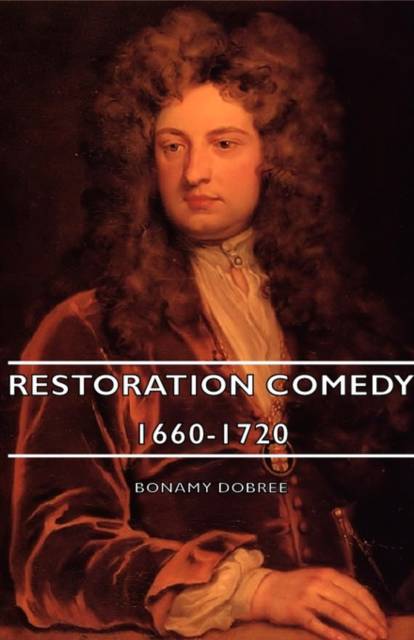

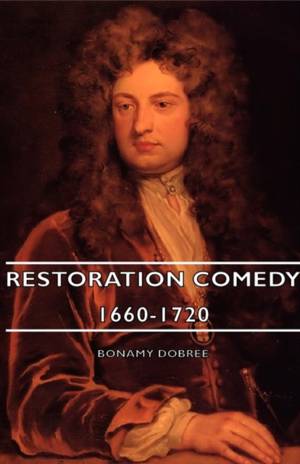

In the history of dramatic literature there are some periods that can be labelled as definitely 'tragic', others as no less preponderatingly 'comic', though of course both forms exist side by side throughout the ages. Taking the period of Aeschylus, Shakespeare, and Corneille as markedly 'tragic', we find that these writers throve in a period of great national expansion and power, during which values were fixed and positive. At such times there is a general acceptation of what is good and what is evil. Out of this, as a kind of trial of strength, there arises tragedy, the positive drama; there is, as Nietzsche suggested, 'an intellectual predilection for what is hard, awful, evil, problematical in existence owing to ... fulness of life'. In the great 'comic' periods, however, those of Menander, of the Restoration writers, and at the end of Louis XIV's reign and during the Regency, we find that values are changing with alarming speed. The times are those of rapid social readjustment and general instability, when policy is insecure, religion doubted and being revised, and morality in a state of chaos. Yet the greatest names in comedy, Aristophanes, Jonson, Moliere, do not belong here: these men flourished in intermediate periods, in which the finest comedy seems to be written. In form it still preserves some of the broad sweep of tragedy and is sometimes hardly to be distinguished from the latter in its philosophy, its implications, and its emotional appeal. Think of The Silent Woman or Le Festin de Pierre. In this period we find that tragedy has lost its positive character, and begins to doubt if the old values are, after all, the best. It begins to have a sceptical or a plaintive note, as in Euripides, Ford, and Racine. Values are beginning to change they are not yet tottering.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 260

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781443727242

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 4/11/2008

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 140 mm x 216 mm

- Gewicht:

- 476 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 69 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.