- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

€ 114,95

+ 229 punten

Omschrijving

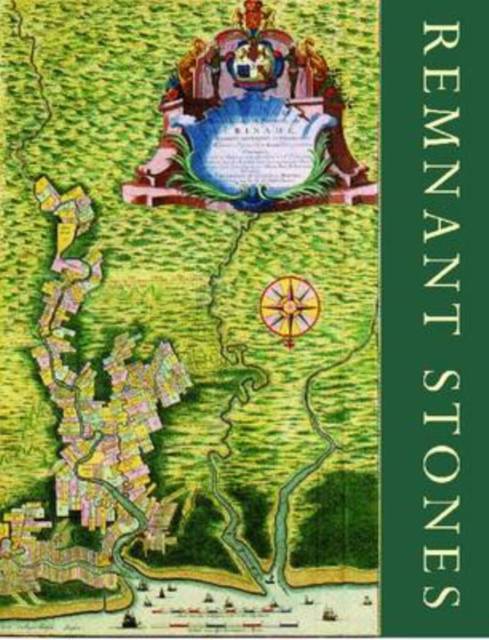

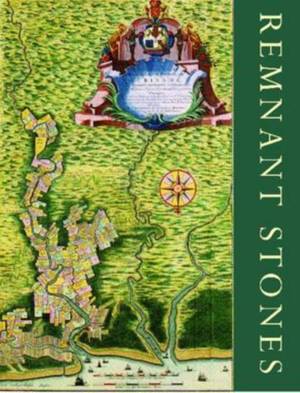

In the 1660s, Jews of Iberian ancestry, many of them fleeing Inquisitorial persecution, established an agrarian settlement in the midst of the Surinamese tropics. The heart of this community-Jodensavanne, or Jews' Savannah-became an autonomous village with its own Jewish institutions, including a majestic synagogue consecrated in 1685. Situated along the Suriname River, some fifty kilometers south of the capital city of Paramaribo, Jodensavanne was by the mid-eighteenth century surrounded by dozens of Jewish plantations sprawling north- and southward and dominating the stretch of the river. These Sephardi-owned plots, mostly devoted to the cultivation and processing of sugar, carried out primarily by enslaved Africans, collectively formed the largest Jewish agricultural community in the world at the time and the only Jewish settlement in the Americas granted virtual self-rule. Sephardi settlement paved the way for the influx of hundreds of Ashkenazi Jews, who began to emigrate in the late seventeenth century from western and central Europe. Generally banned from Jodensavanne, these newcomers settled in Paramaribo, where they established their own cemeteries and historic synagogue. Meanwhile, slave rebellions, Maroon attacks, the general collapse of Suriname's economy, soil depletion, absentee land ownership, and a ravaging fire all contributed to the demise of the old Savannah settlement beginning in the second half of the eighteenth century..

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 680

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780878202249

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/05/2009

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Ongenaaid / garenloos gebonden

- Afmetingen:

- 224 mm x 290 mm

- Gewicht:

- 2558 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 229 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.