- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

€ 15,95

+ 31 punten

Omschrijving

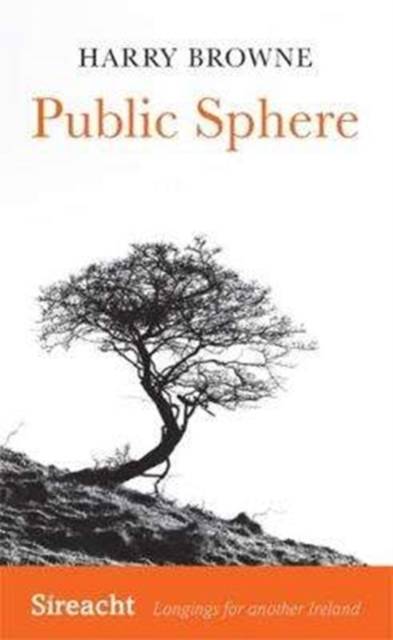

This book is a critique of the public sphere, both as the centrepiece of some liberal theory about political communications, and as a description of actually existing media practice in Ireland and beyond - in traditional commercial news media and in social media. Written in an accessible style, but with endnotes as necessary, it is a call to more and deeper critical thinking about media, old and new, as well as a consideration of the communicative needs of a present and future movement for transformative political and economic change.

The book introduces the public sphere as an historic idea and ideal, a place where democratic subjects deliberate and ensure civil society has a voice at the table of state. It challenges that idea, both in terms of its limitations in a globalised economy and its ultimately technocratic-consensual model of politics, its evasion of what Laclau and Mouffe call 'the ineradicability of antagonism'. It also begins a political-economy critique of the media, the presumed home of the public sphere in the post-18th-century-coffeehouse era.

What we can and can't learn by looking at media behaviour through the lens of its proprietors' commercial interests is discussed. The biases of broadcasters and newspapers in the recent economic crisis are considered, along with the pressures and consequences of declining print circulation and migration of advertising online, as well as some initial questions about pluralism and the continuing important role of the public service media, in Ireland and elsewhere. This chapter includes an extensive review of previously unpublished results of a study into newspaper coverage of the Irish movement against the Iraq war.

Public Sphere also moves the discussion online, where, though nearly infinite pluralism appears to rule the day, power and freedom are more elusive. Under the regime of 'communicative capitalism', we are all 'content providers', generally without remuneration. The continuing centrality of advertising and corporate power in digital media underlines the need to keep our eyes on the money even when talking about a networked information environment. The familiar question of whether online engagement acts as a substitute for 'real world' politics is supplemented, in this chapter, with an examination of the 'real' content of virtual politics, and of whether we can explain some of the weirdest recent turns in the global political journey in light of special features of the online world, such as the 'fake news' that is widely supposed to have elected Donald Trump.

Finally, we look at media alternatives, if any, to the corporate control of potentially transformative communications. Although I regard the concept of the public sphere as hopelessly inadequate at best, I do, in keeping with the theme of the Sireacht series, seek to imagine a healthier environment for public communication in the context of a better Ireland and a better world.

The book introduces the public sphere as an historic idea and ideal, a place where democratic subjects deliberate and ensure civil society has a voice at the table of state. It challenges that idea, both in terms of its limitations in a globalised economy and its ultimately technocratic-consensual model of politics, its evasion of what Laclau and Mouffe call 'the ineradicability of antagonism'. It also begins a political-economy critique of the media, the presumed home of the public sphere in the post-18th-century-coffeehouse era.

What we can and can't learn by looking at media behaviour through the lens of its proprietors' commercial interests is discussed. The biases of broadcasters and newspapers in the recent economic crisis are considered, along with the pressures and consequences of declining print circulation and migration of advertising online, as well as some initial questions about pluralism and the continuing important role of the public service media, in Ireland and elsewhere. This chapter includes an extensive review of previously unpublished results of a study into newspaper coverage of the Irish movement against the Iraq war.

Public Sphere also moves the discussion online, where, though nearly infinite pluralism appears to rule the day, power and freedom are more elusive. Under the regime of 'communicative capitalism', we are all 'content providers', generally without remuneration. The continuing centrality of advertising and corporate power in digital media underlines the need to keep our eyes on the money even when talking about a networked information environment. The familiar question of whether online engagement acts as a substitute for 'real world' politics is supplemented, in this chapter, with an examination of the 'real' content of virtual politics, and of whether we can explain some of the weirdest recent turns in the global political journey in light of special features of the online world, such as the 'fake news' that is widely supposed to have elected Donald Trump.

Finally, we look at media alternatives, if any, to the corporate control of potentially transformative communications. Although I regard the concept of the public sphere as hopelessly inadequate at best, I do, in keeping with the theme of the Sireacht series, seek to imagine a healthier environment for public communication in the context of a better Ireland and a better world.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 160

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

- Reeksnummer:

- nr. 2

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781782052432

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/02/2018

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 196 mm x 190 mm

- Gewicht:

- 140 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 31 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.