- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

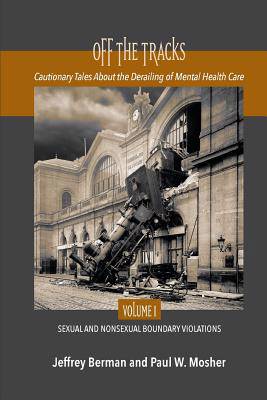

Off the Tracks

Cautionary Tales About the Derailing of Mental Health Care Volume 1 Sexual and Nonsexual

Jeffrey Berman, Paul W MosherOmschrijving

Psychiatry has much in common with the irresistible little girl Henry Wadsworth Longfellow immortalized in a poem that became a household nursery rhyme: "When she was good, she was very good indeed, / But when she was bad she was horrid." The same can be said for the mental health profession.

Despite numerous advances in the past century, the treatment of mental disorders is still in a rudimentary state due to our fundamental lack of understanding of the complex causes of some of its daunting problems. Most mental health professionals now believe that both psychological (psychodynamic) and physical (inherited or biomedical)

factors combine in varying proportions to undermine a person's state of emotional well-being. Most experts also believe that an optimal combination of psychological and physical treatments will provide for many patients the best chance of recovery. Across this wide spectrum of possible combinations, the one factor that appears to be most crucial to recovery is the treatment relationship.

Many studies of purely psychological treatments have shown that the treatment relationship is the single most important variable in determining therapy outcome. "The therapy relationship accounts for why clients improve--or fail to improve--as much as the particular treatment method," a major review of "Evidence-Based Therapy

Relationships" concludes. Thousands of qualitative and quantitative studies have demonstrated that about 75-80% of patients who enter psychotherapy show improvement, a treatment outcome well above that of many medical procedures. It is self-evident, then, that the treatment relationship must be a powerful force in and of itself. Like any powerful force, the management or mismanagement of the treatment relationship can bring great benefit or harm to the patient. Off the Tracks: Cautionary Tales About the Derailing of Mental Health Care presents dramatic examples, across a broad range of theoretical approaches to mental health care, where the treatment relationship was mismanaged in such a way as to harm mentally ill patients. We are not presenting these examples to condemn psychoanalytic, psychiatric or psychological treatments, but rather to show how these cautionary tales

indicate the necessity of self-monitoring and self-regulation by members of the mental health profession. Because we speak here of a relationship, the extent to which the personality of the therapist is implicated makes

the requirements of the therapist unique in the world of health care. We are not limiting ourselves only to the role of the therapist in purely psychological treatments. In the realm of predominantly physical treatments of mental disorders, clinicians delivering the treatment are psychotherapists as well. Clinicians' judgments in choosing a physical approach or a pharmacological agent, determining its frequency or dose, or even deciding how often they see their patients, are clearly related to the relationship as much as to the underlying scientific theory supposedly governing such choices .

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 510

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781949093155

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 21/01/2019

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Gewicht:

- 675 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.