- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

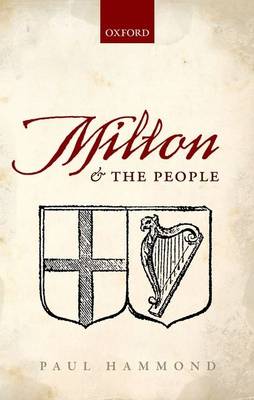

Who are 'the people' in Milton's writing? They figure prominently in his texts from early youth to late maturity, in his poetry and in his prose works; they are invoked as the sovereign power in the state and have the right to overthrow tyrants; they are also, as God's chosen people, the guardians of the true Protestant path against those who would corrupt or destroy the Reformation. They are entrusted with the preservation of liberty in both the secular and the spiritual spheres. And yet Milton is uncomfortably aware that the people are rarely sufficiently moral, pure, intelligent, or energetic to discharge those responsibilities which his political theory and his theology would place upon them. When given the freedom to choose, they too often prefer servitude to freedom. Milton and the People traces the twists and turns of Milton's terminology and rhetoric across the whole range of his writings, in verse and prose, as he grapples with the problem that the people have a calling to which they seem not to be adequate. Indeed, they are often referred to not as 'the people' but as 'the vulgar', as well as 'the rude multitude', 'the rabble', and even as 'scum'. Increasingly his rhetoric imagines that liberty or salvation may lie not with the people but in the hands of a small group or even an individual. An additional thread which runs through this discussion is Milton's own self-image: as he takes responsibility for defining the vocation of the people, and for analysing the causes of their defection from that high calling, his own role comes under scrutiny both from himself and from his enemies.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 286

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780199682379

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 29/07/2014

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 139 mm x 229 mm

- Gewicht:

- 480 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 296 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.