- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

€ 22,45

+ 44 punten

Omschrijving

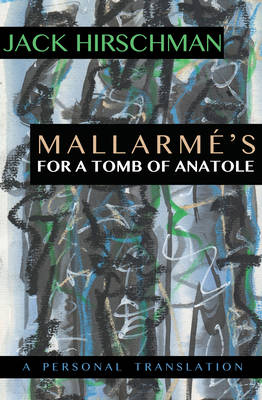

Mallarmé's second child, Anatole, born July 1871, became seriously ill when he was seven years old. He suffered from rheumatic fever complicated by an enlarged heart, and died in October 1879, aged eight. Mallarmé wrote a series of grief-stricken fragments for what was planned to be a long poem in four parts. The poem was never completed, and the fragments were not published in France until 1961, when it appeared as Pour Un Tombeau d'Anatole. Poet Jack Hirschman first translated this work in the 1970s, and then tragically lost his own son, David, to leukemia in 1982. In his commentary that accompanies this translation, written one month after his son's passing, Hirschman reflects on the pain of a parent who has lost a child, and his grief is palpable. According to Hirschman, Mallarmé has written himself into contemporary 20th century voice with this book, and in such a way to give comfort and meaning to all those who experience the dark passage of grief at the loss of one close to the heart. Hirschman wrote out the translation by hand, reflecting Mallarmé's placement of words on the page, and his handwritten work is what appears in this book, adding to its personal nature.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 224

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781945665134

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 18/12/2018

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 137 mm x 213 mm

- Gewicht:

- 226 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 44 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.