- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

€ 90,95

+ 181 punten

Uitvoering

Omschrijving

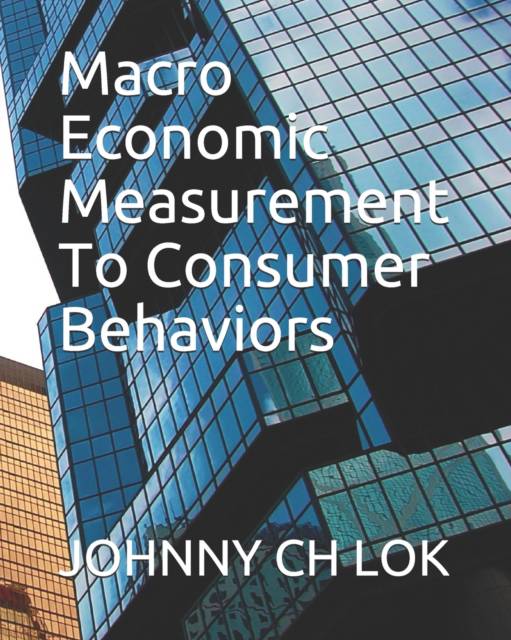

Concerning how to examine the impact of legitimate labor market experiences (e.g., unemployment) and sanctions on criminal behavior whether they have relationship question? Broadly speaking, the empirical findings are that (i) poor legitimate labor market opportunities of potential criminals, such as low wages and high rates of unemployment, increases the supply of criminal activities and (ii) sanctions deter crime. Unemployment could be taken to influence the opportunity cost of illegal activity. High rates of unemployment growth could be taken to imply a restriction on the availability of legal activities, and thus serve to ultimately reduce the opportunity cost of engaging in illegal activities. Although theoretically well-defined, most empirical studies of the unemployment-crime relationship have provided mixed evidence. Instead of primarily focusing on crime as a function of unemployment, they use a richer set of controls, like deterrence, employment status, age, education, race and neighbourhood characteristics. One problem with most work and crime models is that they assume bothactivities are mutually exclusive. This may be a problematic assumption when considering disadvantaged youths. The fact that a youth can shift from crime to an unskilled job and back again or can commit crime while holding a legal job means that the supply of youths to crime will be quite elastic with respect to relative rewards from crime vis-a-vis legal work or to the number of criminal opportunities. From the 1970s through the 1990s the labor market prospects for unskilled workers in most OECD countries has deteriorated considerably. In particular, the real earnings of young unskilled men fell, while income inequality rose. This suggests that as the earnings gap widens, relative deprivation increases, which in turn leads toincreases in crime. A substantial problem that has been ignored in the vast majority of empiricalstudies is nonstationarity of crime rates. A time-series is said to be nonstationary if (1)the mean and/or variance does not remain constant over time and (2) covariancebetween observations depends on the time at which they occur. In the US, the indexcrime rate appears strongly nonstationary, for the most part being integrated of orderone with both deterministic and stochastic trends (a random variable whose meanvalue and variance are time-dependent is said to follow a stochastic trend) .The empirical results suggest a long-run equilibrium relationship between crime, prison population, female labor supply and durable consumption.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 372

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781710412833

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 22/11/2019

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 203 mm x 254 mm

- Gewicht:

- 1020 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 181 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.