Je cadeautjes zeker op tijd in huis hebben voor de feestdagen? Kom langs in onze winkels en vind het perfecte geschenk!

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Je cadeautjes zeker op tijd in huis hebben voor de feestdagen? Kom langs in onze winkels en vind het perfecte geschenk!

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

€ 39,00

+ 78 punten

Omschrijving

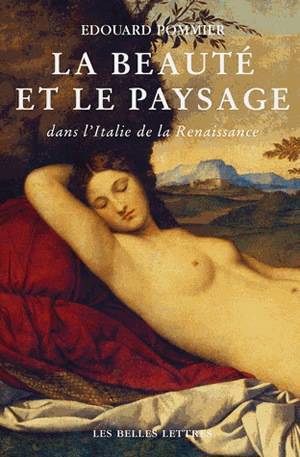

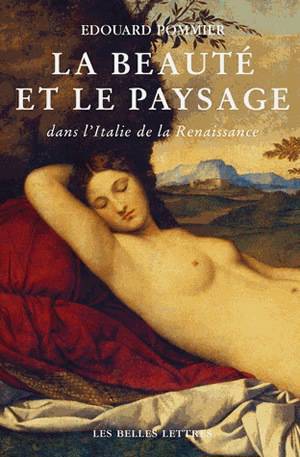

English summary: "The masterpiece of the painter is the representation of a story." This serene and majestic affirmation by Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), taken from his De Pictura, is at the foundations of the Italian and European schools of thought of painting from the beginning of the Renaissance to the end of the neo-classicist period; in Italian Renaissance literature, the landscape is not considered fully as a genre. Consequently, is the humanist conception of painting, which essentially refers to human actions, compatible with man's entrance into the outer world from the point of view of the painter? This is exactly the question the book answers, addressing it both with finesse and erudition. French text. French description: Le grand oeuvre du peintre, c'est la representation d'une histoire. La peinture a en elle une force toute divine. Ces deux affirmations sereines et majestueuses de Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), tirees de son De pictura, ecrit en latin en 1435, puis en italien l'annee suivante, sont fondatrices de toute la pensee italienne, et donc europeenne, sur la peinture, du debut de la Renaissance a la fin du neo-classicisme: le paysage n'est pas considere comme un genre a part entiere dans la litterature artistique italienne de la Renaissance. Pourtant en identifiant la noblesse de la peinture a son pouvoir de derouler devant nos yeux l'histoire du salut de l'humanite, les mythes et les histoires antiques, et en fondant son caractere divin sur sa fonction memoriale, Alberti n'a-t-il pas laisse une place a ce que nous appelons, d'un terme qu'il ne connaissait pas, la peinture de paysage, c'est-a-dire l'art de representer le spectacle de l'univers naturel. Autrement dit, la conception humaniste de la peinture, qui se refere essentiellement aux actions des hommes, est-elle compatible avec l'entree du monde exterieur aux hommes dans le champ du regard du peintre? Telle est la question a laquelle repond ce livre tout en finesse et en erudition. En fait, l'interet pour la representation de la nature se manifeste d'abord avec la question du pouvoir de la peinture, en particulier dans le cadre du debat sur le Paragone visant a elire le premier des arts (entre la sculpture, l'architecture et la peinture). Dans cette perspective, c'est la nature en action, la nature meteorologique, la tempete par exemple, qui interesse les theoriciens. Mais en meme temps l'utilisation, en milieu venitien, du terme paese pour designer le paysage en peinture montre que l'attention se porte avant tout sur la representation d'une nature habitee et ordonnee par l'homme, d'un territoire, meme si cette image ne devient pas encore le sujet d'un tableau autonome.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 191

- Taal:

- Frans

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9782251420486

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 7/12/2012

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 150 mm x 220 mm

- Gewicht:

- 801 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 78 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.