- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

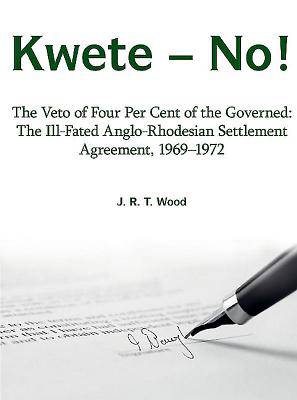

Kwete - No!

The Veto of Four Per Cent of the Governed: The Ill-Fated Anglo-Rhodesian Settlement Agreement, 1969-1972

Richard Wood

Paperback | Engels

€ 62,95

+ 125 punten

Omschrijving

The adoption of the new republican constitution by the Rhodesian electorate in 1969 was intended to end the fruitless four-year-long negotiations with the British to secure recognition of the unilateral declaration of independence by Ian Smith on 11 November 1965. Given the evasion by significant nations of the trade sanctions imposed by the United Nations, the gamble was that this de facto recognition would become de jure. Formal recognition, needless to say, was unlikely because the framers of the 1969 constitution rejected the established aim of progress to majority rule through a qualified franchise. Instead they offered the Africans only the goal of parity of racial representation, despite the whites amounting to four per cent of the population. Accordingly, the 46-year-old nonracial common roll was replaced by a separate African roll and a 'European' one which included, incongruously, the small Asian and colored populations for the purposes of the vote only. In addition, the African ability to qualify for the vote was governed by the ratio of income tax they paid in comparison with the 'Europeans'. Perhaps because this arrangement was certain to be unacceptable internationally, Ian Smith, the Rhodesian prime minister, welcomed a secret overture in 1970 from the new British Conservative government of Edward Heath to reopen the Anglo-Rhodesian negotiations. The British negotiating team, led by the lawyer, Lord Goodman, succeeded by November 1972 to secure an agreed compromise that restored the aim of eventual majority rule. The exiled Rhodesian African nationalist insurgents, the Zimbabwe African People's Union and the Zimbabwe African National Union, had adopted in 1962 the Marxist prescription of the armed struggle as the path to power. Their efforts, however, to ignite an armed insurgency and to make Rhodesia ungovernable were petering out by the time of the Anglo-Rhodesian settlement in late November 1972. It therefore fell to the African nationalists within Rhodesia, also bent on immediate African majority rule, to stymie the settlement effort. They succeeded because the British insisted from the outset that any settlement had to be endorsed by the majority of the people of Rhodesia. Because Ian Smith would not hold a referendum as it would mean conceding 'one man one vote', the assessment of opinion was left to a British judicial commission led by Lord Pearce. The British insistence on 'normal political activity' during the test forced Smith to release from preventive detention a significant number of African nationalist activists. The leisurely formation of the commission allowed these activists sufficient time to organize a campaign of rejection, the result of which the Pearce Commission could not or chose not to ignore.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 576

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781910294970

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 19/07/2015

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 208 mm x 295 mm

- Gewicht:

- 1428 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 125 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.