- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

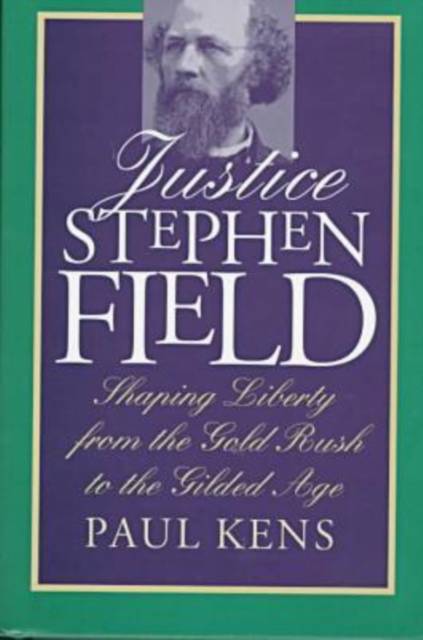

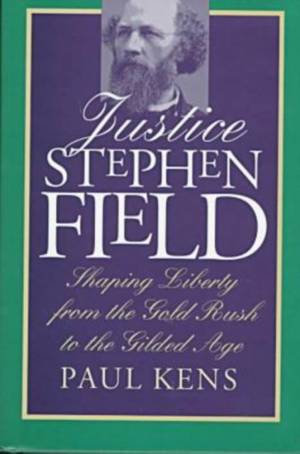

Justice Stephen Field

Shaping Liberty from the Gold Rush to the Gilded Age

Paul Kens

Hardcover | Engels

€ 101,95

+ 203 punten

Omschrijving

Outspoken and controversial, Stephen Field served on the Supreme Court from his appointment by Lincoln in 1863 through the closing years of the century. No justice had ever served longer on the Court, and few were as determined to use the Court to lead the nation into a new and exciting era. Paul Kens shows how Field ascended to such prominence, what influenced his legal thought and court opinions, and why both are still very relevant today. One of the famous gold rush forty-niners, Field was a founder of Marysville, California, a state legislator, and state supreme court justice. His decisions from the state bench and later from the federal circuit court often placed him in the middle of tense conflicts over the distribution of the land and mineral wealth of the new state. Kens illuminates how Field's experiences in early California influenced his jurisprudence and produced a theory of liberty that reflected both the ideals of his Jacksonian youth and the teachings of laissez-faire economics. During the time that Field served on the U.S. Supreme Court, the nation went through the Civil War and Reconstruction and moved from an agrarian to an industrial economy in which big business dominated. Fear of concentrated wealth caused many reformers of the time to look to government as an ally in the preservation of their liberty. In the volatile debates over government regulation of business, Field became a leading advocate of substantive due process and liberty of contract, legal doctrines that enabled the Court to veto state economic legislation and heavily influenced constitutional law well into the twentieth century. In the effort to curb what he viewed as the excessive power of government, Field tended to side with business and frequently came into conflict with reformers of his era. Gracefully written and filled with sharp insights, Kens' study sheds new light on Field's role in helping the Court define the nature of liberty and determine the extent of constitutional protection of property. By focusing on the political, economic, and social struggles of his time, it explains Field's jurisprudence in terms of conflicting views of liberty and individualism. It firmly establishes Field as a persuasive spokesman for one side of that conflict and as a prototype for the modern activist judge, while providing an important new view of capitalist expansion and social change in Gilded Age America.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 384

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780700608171

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 25/04/1997

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 168 mm x 241 mm

- Gewicht:

- 811 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 203 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.