- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Omschrijving

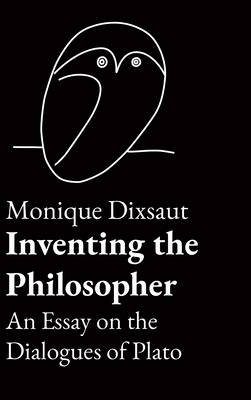

It may well be that what we call philosophy has little to do with what Plato calls philosophia. For him, philosophy never has been nor will be assured of its possibility, nor its reality, nor its definition, nor even its name: the only thing certain about it is that it is necessary, and necessary only for itself.

By opposing an etymology that makes philosophy a "desire to know" or a "love of wisdom," and believes thereby to have said all that needs be said about it, Plato explores all the implications of a word for which he invented the "philosophic" sense.

So this book means to do two things at the same time. It attempts to determine the different meanings given by Plato to the word philosophia, designating in the first dialogues the obstinate force that animates the figure of Socrates; and from the Phaedo to the Phaedrus receives its interior dimensions - the destructive irony of a philosophical nature allied with a mad delirium both erotic and resourceful; and in the end has its dialectical and interrogative modality articulated at the same time that its political and cosmological implications are drawn. But to see in the dialogues the invention of a philosophia that is becoming conscious of its own power requires also that one divert his attention from any doctrinal content and toward the manner in which the problems are posed and re-posed, thought and re-thought, and then rewards him for doing so.

The entire purpose of this enterprise is therefore to invite the reader to read, freely and scrupulously, texts as subtly baffling, as voluntarily fragmented, as multiply mediated as they can be.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 362

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781680538229

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 28/11/2022

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Gewicht:

- 653 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.