- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

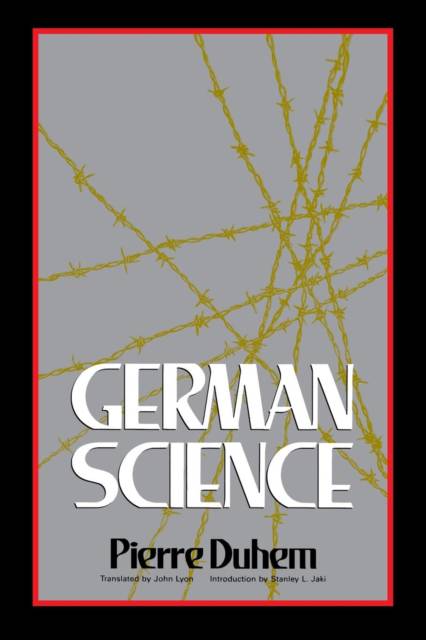

German Science

Some Reflections on German Science/German Science and German Virtues

Pierre Duhem

Paperback | Engels

€ 27,95

+ 55 punten

Omschrijving

More than any other major twentieth-century writer, Pierre Duhem has been the victim of ill-informed guesswork. For instance, many references to Duhem stress the importance of his Catholic faith, but nearly all of them draw the obvious -- and entirely erroneous -- conclusions about the role of Catholicism in Duhem's thinking. Dr. Martin's study of Pierre Duhem's work is the fruit of many years of painstaking research. The author's approach is cautious, yet his conclusions are surprising, and refute many prevailing legends abut Duhem. The real Duhem, however, is even more fascinating than the legendary one. This book pays particular attention to the political and intellectual context of French Catholicism, wracked as it was by tensions of the Dreyfuss affair and the so-called modernistic crisis. Duhem took his inspiration, not from the papally-sponsored revival of the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, but from Pascal, a fact that aroused suspicions of skepticism in the minds of conservative Catholics. The tensions between Duhem's work and authoritarian Catholic positions became more explicit as his historical work unfolded. Most famous for his denial of the possibility of a crucial experiment which could unambiguously decide between contending scientific theories, Duhem has often been interpreted as a mere instrumentalist or conventionalist, denying the meaningfulness of a reality behind the theory. Dr. Martin shows that Duhem was a Pascalian who argued for both logic and intuition as indispensable in approaching the truth. Duhem argued that physics could not legitimately be used to attack Christianity, but he held that physics was equally useless for the defense of Christianity, a position which made him unpopular with many Catholics. Duhem is now well-known for his historical work refuting the myth that there was no medieval science. Duhem demonstrated that figures like Leonardo and Galileo were not isolated pioneers; far from being the founder of a new science, they were continuing a tradition of the scientific work that had been developing for centuries. It has been surmised that Duhem was predisposed to rehabilitate medieval science for apologetic motives. Martin shows that Duhem's discovery of medieval science can be dated to within a month, and came as a complete surprise to him, changing the whole course of his work, and introducing an abrupt discontinuity between his earlier and his later preoccupations. Furthermore, Duhem's findings in medieval intellectual history have proved indigestible ever since, to believers and unbelievers alike.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Vertaler(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 164

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780812691245

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 10/05/1991

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 155 mm x 232 mm

- Gewicht:

- 258 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 55 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.