- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

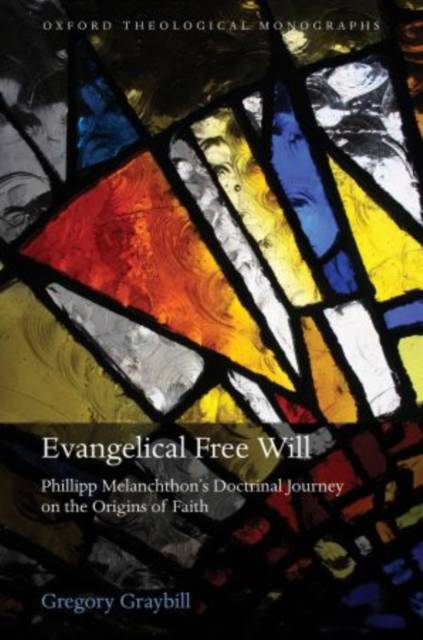

Evangelical Free Will

Philipp Melanchthon's Doctrinal Journey on the Origins of Faith

Gregory B Graybill

€ 233,95

+ 467 punten

Omschrijving

If one is saved by faith alone in Jesus Christ, then what is the origin of that faith? Is it a preordained gift of God to elect individuals, or is some measure of human free choice involved? The debate over the relation between election and free will has a central place in the study of Reformation theology. Phillipp Melanchthon's reputation as the intellectual founder of Lutheranism has tended to obscure the differences between the mature doctrinal positions of Melanchthon and Martin Luther on this key issue. Gregory Graybill charts the progression of Melanchthon's position on free will and divine predestination as he shifts from agreement to an important innovation upon Luther's thought. Initially Melanchthon concurred with Luther that the human will is completely bound by sin, and that the choice of faith can flow only from God's unilateral grace. Over time, this understanding caused Melanchthon increasing concern. The problem of its eternal implications for those whom God has not chosen, and its pastoral implications for believers, combined with Melanchthon's own intellectual aversion to paradox and prompted him to continue developing his ideas. Melanchthon came to believe that the human will does play a key role in the origins of a saving faith in Jesus Christ. This was not the Roman Catholic free will of Erasmus, rather it was belief in a limited free will tied to justification by faith alone; an evangelical free will.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 368

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780199589487

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 3/09/2010

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 170 mm x 150 mm

- Gewicht:

- 712 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 467 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.