- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

€ 37,95

+ 75 punten

Omschrijving

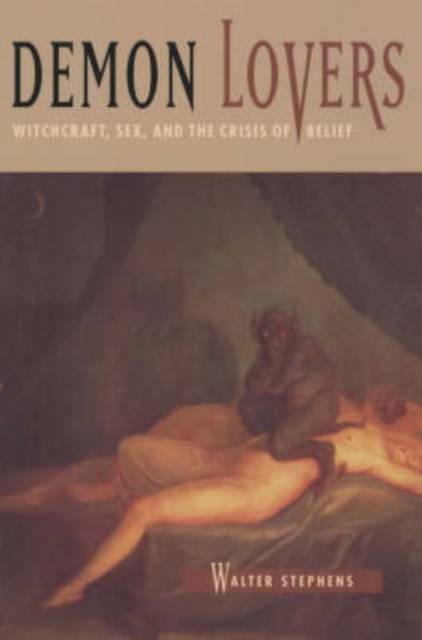

On September 20, 1587, Walpurga Hausmännin of Dillingen in southern Germany was burned at the stake as a witch. Although she had confessed to committing a long list of maleficia (deeds of harmful magic), including killing forty--one infants and two mothers in labor, her evil career allegedly began with just one heinous act--sex with a demon. Fornication with demons was a major theme of her trial record, which detailed an almost continuous orgy of sexual excess with her diabolical paramour Federlin in many divers places, . . . even in the street by night. As Walter Stephens demonstrates in Demon Lovers, it was not Hausmännin or other so-called witches who were obsessive about sex with demons--instead, a number of devout Christians, including trained theologians, displayed an uncanny preoccupation with the topic during the centuries of the witch craze. Why? To find out, Stephens conducts a detailed investigation of the first and most influential treatises on witchcraft (written between 1430 and 1530), including the infamous Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches). Far from being credulous fools or mindless misogynists, early writers on witchcraft emerge in Stephens's account as rational but reluctant skeptics, trying desperately to resolve contradictions in Christian thought on God, spirits, and sacraments that had bedeviled theologians for centuries. Proof of the physical existence of demons--for instance, through evidence of their intercourse with mortal witches--would provide strong evidence for the reality of the supernatural, the truth of the Bible, and the existence of God. Early modern witchcraft theory reflected a crisis of belief--a crisis that continues to be expressed today in popular debates over angels, Satanic ritual child abuse, and alien abduction.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 478

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780226772622

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 15/08/2003

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 153 mm x 232 mm

- Gewicht:

- 630 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 75 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.