Door een staking bij bpost kan je online bestelling op dit moment iets langer onderweg zijn dan voorzien. Dringend iets nodig? Onze winkels ontvangen jou met open armen!

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Door een staking bij bpost kan je online bestelling op dit moment iets langer onderweg zijn dan voorzien. Dringend iets nodig? Onze winkels ontvangen jou met open armen!

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

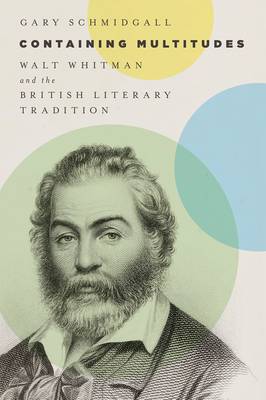

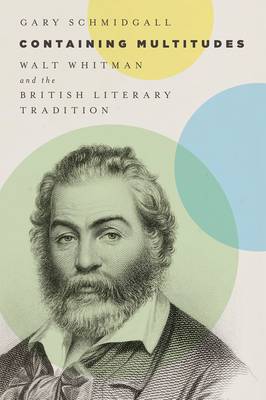

Containing Multitudes

Walt Whitman and the British Literary Tradition

Gary Schmidgall

Hardcover | Engels

€ 125,45

+ 250 punten

Omschrijving

Walt Whitman burst onto the literary stage raring for a fight with his transatlantic forebears. With the unmetered and unrhymed long lines of Leaves of Grass, he blithely forsook "the old models" declaring that "poems distilled from other poems will probably pass away." In a self-authored but unsigned review of the inaugural 1855 edition, Whitman boasted that its influence-free author "makes no allusions to books or writers; their spirits do not seem to have touched him." There was more than a hint here of a party-crasher's bravado or a new-comer's anxiety about being perceived as derivative. But the giants of British literature were too well established in America to be toppled by Whitman's patronizing "that wonderful little island," he called England-or his frequent assertions that Old World literature was non grata on American soil. As Gary Schmidgall demonstrates, the American bard's manuscripts, letters, prose criticism, and private conversations all reveal that Whitman's negotiation with the literary "big fellows" across the Atlantic was much more nuanced and contradictory than might be supposed. His hostile posture also changed over the decades as the gymnastic rebel transformed into Good Gray Poet, though even late in life he could still crow that his masterwork Leaves of Grass "is an iconoclasm, it starts out to shatter the idols of porcelain." Containing Multitudes explores Whitman's often uneasy embrace of five members of the British literary pantheon: Shakespeare, Milton, Burns, Blake, and Wordsworth (five others are treated more briefly: Scott, Carlyle, Tennyson, Wilde, and Swinburne). It also considers how the arcs of their creative careers are often similar to the arc of Whitman's own fifty years of poem-making. Finally, it seeks to illuminate the sometimes striking affinities between the views of these authors and Whitman on human nature and society. Though he was loath to admit it, these authors anticipated much that we now see as quintessentially Whitmanic.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 400

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780199374410

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 25/11/2014

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 234 mm x 165 mm

- Gewicht:

- 733 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 250 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.