- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

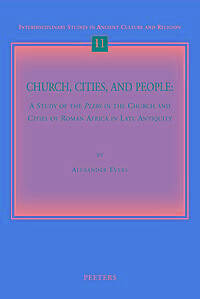

Church, Cities, and People

A Study of the Plebs in the Church and Cities of Roman Africa in Late Antiquity

A Evers

€ 123,95

+ 247 punten

Omschrijving

This book is about people. It is an attempt to make sense of the position of the plebs in the Church and cities of Roman Africa in Late Antiquity. By looking at the terminology of plebs and populus in Christian texts, in combination with aspects of the vast amount of archaeological evidence and epigraphy from the African provinces of the Roman Empire, Evers seeks to establish a much closer link between text and context, arguing that the laity in the Early Church had an active role to play. The writings of Cyprian of Carthage, Optatus of Milevis, and Augustine of Hippo are taken more at face value, and not discarded as purely theological treatises and other programmatic products of the Christian pen. Christian texts, certainly of earlier times, most of all aimed at convincing an audience as large as possible, of all sorts, and of all ranks. And hence they must have made sense in almost every possible way. The rhetoric of Empire became rapidly adapted by the great minds of the Early Church to the needs of Christianity. But this rhetoric was not simply an artificial language, transmitted and maintained throughout the centuries, creating a world that was merely recognisable through memory. The written and spoken words of bishops, priests, and other Christian figures of authority, following the example of their secular counterparts, were not simply compositions of eschatological fiction. Their works continued to refer to real, social, political, and cultural frameworks outside the texts, as is established by the archaeological and epigraphic evidence. Both plebs and populus continued to have significant social and political connotations. The conversion of Emperor Constantine did not bring about a rapid change. Orthodoxy, and hence authority, was not established and secured overnight. The ecclesiastical hierarchy, moulded over centuries, and with the structures of Empire as its prime example, continued to depend on the people within the Church, even until Augustine's time and beyond. Arguably, the position of the plebs Christiana was a reflection of that of the plebs urbana, the people in the cities of Roman Africa. The Empire and its cities acted as a model for the Church, hence the Church became a mirror for the cities and the Empire.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 367

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

- Reeksnummer:

- nr. 11

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9789042922068

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 21/01/2010

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 157 mm x 239 mm

- Gewicht:

- 635 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 247 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.