- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Omschrijving

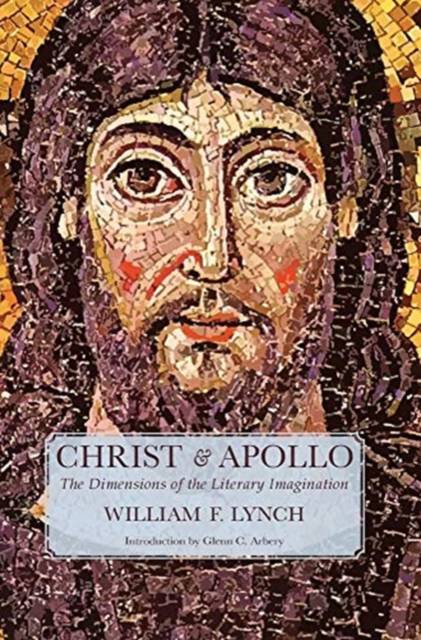

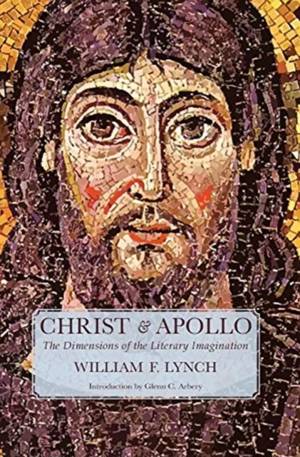

Christ and Apollo juxtaposes Christian definiteness to romantic mythologizing. A strong warning might be in order: anyone coming to this book expecting a comparison of Jesus Christ to the god Apollo or a treatment of Greek mythology next to the Christian story will be disappointed. Lynch's Apollo is not the god who batters Achilles' armor from the shoulders of Patroklos in Book XVI of the Iliad, but the symbol of art as dream reconceived by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy. Lynch treats Apollo not as a poetic particular-as real in that regard as Ajax or Odysseus-but as an imaginary deity over against the historical existence of Christ:

"I take even the symbol of Apollo as a kind of infinite dream over against Christ who was full of definiteness and actuality-and was on that account rejected by every gnostic system since, even up to now. Even if a little unjustly, let Apollo stand for everything that is weak and pejorative in the 'aesthetic man' of Kierkegaard and for that kind of fantasy beauty which is a sort of infinite, which is easily gotten everywhere, but which will not abide the straitened gates of limitation that leads to stronger beauty."

Christ and Apollo presents these "straitened gates of limitation" as the great good of literature. Insisting on the "universal limitation, or particularity" that provokes the response of the imagination, Lynch writes that "the heart, substance, and center of the human imagination, as of human life, must lie in the particular and limited image or thing." This sui generis study reaches into the very heart of literature's nature, from the Greek dramatists to Dante, from Shakespeare to Proust, from Camus to Greene.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 330

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781951319878

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 4/04/2021

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 127 mm x 203 mm

- Gewicht:

- 439 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.