- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

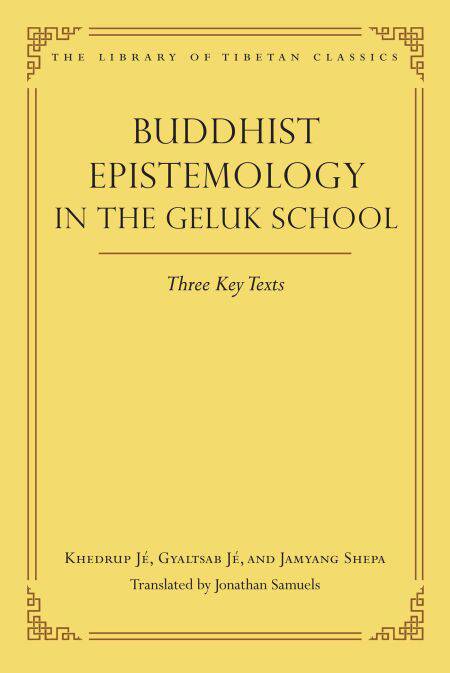

Buddhist Epistemology in the Geluk Schoo E-BOOK

Three Key Texts

Jonathan Samuels, Khedrup Je, Gyaltsab Je, The First Jamyang Shepa

€ 72,69

+ 72 punten

Omschrijving

Tibet’s philosophical tradition is on brilliant display in this anthology of works exploring the means to finding certainty in an impermanent and interdependent world. Here, descendants of the great Tsongkhapa plumb the nature of knowing to harness it in the service of awakening.

This volume includes translations of three separate Tibetan works by iconic figures in the Geluk school of Buddhism. The first work, Banisher of Ignorance, is by Khedrup Gelek Palsang (1385–1438), and the second, On Preclusion and Relationship, is by Gyaltsab Darma Rinchen (1364–1432). The authors—popularly known as Khedrup Je and Gyaltsab Je—were the foremost disciples of the Geluk-school founder, Tsongkhapa Losang Drakpa (1357–1419). The third text, Mighty Pramana Sun, is a commentary on the first chapter of Candrakirti’s Clear Words (Prasannapada) by Jamyang Shepa (1648–1721).

These works concern themselves primarily with the Buddhist theory of knowledge—the means by which we are able to know things and how we can be certain of that knowledge. Encapsulating this theory is the notion of pramana, the Buddhist understanding of which was shaped most significantly by the Indian masters Dignaga (fifth to sixth century) and Dharmakirti (seventh century). Based on their explanation, pramana is often translated as “valid cognition,” a literal reference to the kind of cognition that they proposed could be relied upon to supply indisputable knowledge.

In the Buddhist Pramana tradition, rigorous reasoning is held to play a crucial role in gaining such knowledge, and there is no better exemplar of the sophistication this endeavor achieved in Tibet than Khedrup Je’s work here. He systematically catalogs and rebuts a host of views with unmatched acumen and flair. All three works illustrate how those who follow the tradition have viewed the systematic approach as necessary not only for textual analysis—for those seeking to unravel the complexities of the Indian Buddhist scriptures and treatises—but also for practitioners aiming to progress along the spiritual path and achieve the highest Buddhist goals.

This volume includes translations of three separate Tibetan works by iconic figures in the Geluk school of Buddhism. The first work, Banisher of Ignorance, is by Khedrup Gelek Palsang (1385–1438), and the second, On Preclusion and Relationship, is by Gyaltsab Darma Rinchen (1364–1432). The authors—popularly known as Khedrup Je and Gyaltsab Je—were the foremost disciples of the Geluk-school founder, Tsongkhapa Losang Drakpa (1357–1419). The third text, Mighty Pramana Sun, is a commentary on the first chapter of Candrakirti’s Clear Words (Prasannapada) by Jamyang Shepa (1648–1721).

These works concern themselves primarily with the Buddhist theory of knowledge—the means by which we are able to know things and how we can be certain of that knowledge. Encapsulating this theory is the notion of pramana, the Buddhist understanding of which was shaped most significantly by the Indian masters Dignaga (fifth to sixth century) and Dharmakirti (seventh century). Based on their explanation, pramana is often translated as “valid cognition,” a literal reference to the kind of cognition that they proposed could be relied upon to supply indisputable knowledge.

In the Buddhist Pramana tradition, rigorous reasoning is held to play a crucial role in gaining such knowledge, and there is no better exemplar of the sophistication this endeavor achieved in Tibet than Khedrup Je’s work here. He systematically catalogs and rebuts a host of views with unmatched acumen and flair. All three works illustrate how those who follow the tradition have viewed the systematic approach as necessary not only for textual analysis—for those seeking to unravel the complexities of the Indian Buddhist scriptures and treatises—but also for practitioners aiming to progress along the spiritual path and achieve the highest Buddhist goals.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 904

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781614299561

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 25/08/2025

- Uitvoering:

- E-book

- Beveiligd met:

- Adobe DRM

- Formaat:

- ePub

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 72 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.