- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

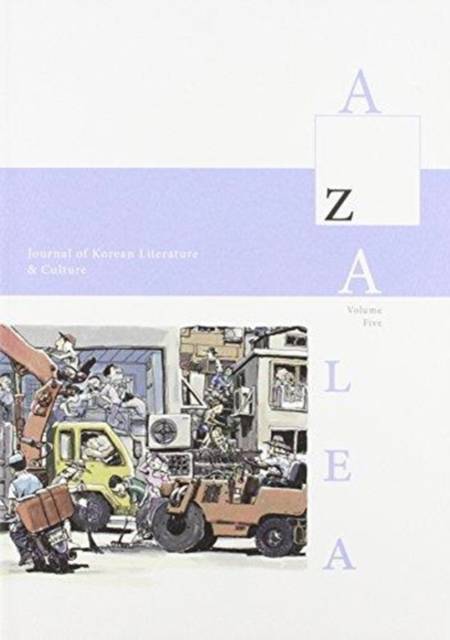

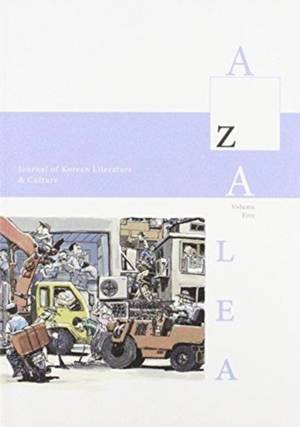

Azalea 5

Journal of Korean Literature and Culture

Omschrijving

As becomes more and more apparent, Korea and Korean cultural and literary practices have been open and engaged for centuries. Korea was part of the complicated, dangerous, and demanding world during the Koryŏ dynasty when Mongol conquest or the threat of it had unfurled from Korea to Vienna. (And as they say still in Vienna, Wien bleibt Wien; Vienna stays Vienna.) Peter Lee in this issue presents an extraordinarily full account of the cultural context of the Koryŏ songs that have come down to us, through a variety of travelways, to register their voices from a time when even in Korea there was not a cell phone to be found anywhere.

What was Korea, Japan, or life like in the twentieth century under Japanese colonial rule? John Frankl has been pursuing that and other questions in his studies and translations of the proto-modernist writer/artist/flâneur Yi Sang. There is something poignantly as well as literally expressive to be found in the scene when Yi Sang the essayist discounts all famous sites in the Japanese capital city as he stands taking a satisfying break at a public toilet. In an old story, a policeman whacks a fellow on the shoulder who was urinating against an alley wall, and points at the sign. "See that? Sobyŏn kŭmji! Urination forbidden!" The old fellow laughs and points, reading the sign in the opposite order: "Chigŏm pyŏnso: Right now, a toilet." In the same earthy and direct manner, Yi Sang the writer, artist, and individual reversed the cultural readings of Korea's colonized state. The present gathering also includes examples of contemporary Korean fiction and poetry, and the reincarnation of Kubo the Novelist from the widely known 1934 fictional work "A Day in the Life of Kubo the Novelist," but in a new form and magazine medium as Kubo the Film Critic, a witty out-take on Korea's current-day film culture. To be able to tell the story, and sing or say the poem, are signs of a culture's freedom, even within the close confines of political or cultural norms imposed from outside. For all its didactic purposes, the example of "The Sky," the 1937 children's story by Hyŏn Tŏk, still gives us voices and events that in turn afford a palpable sense of the life of that time. Just as Peter Lee has done with the details of Koryŏ life and culture that frame the Koryŏ songs, this issue's other stories and poems likewise give the reader a lively sense of Korea's 20th and 21st century literature and culture. The astonishingly vivid images in Choi Ho-Cheol's cartoons deserve their own eloquent praise. One might note the vivid detail, the extraordinary depth, the range and active participation in life by all the figures in the pictures, the sweep of the landscape, from house porch to landmark skyscraper, and suggest that the same range, the same array of vivid details, the same sense of an exuberantly vital cultural community are to be found in all the work of our current issue. We owe thanks to the managing editor for once again assembling such a repast, as well as to the writers, translators, artists, and other participants in this lively issue.Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 376

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780979580086

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 30/09/2012

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Gewicht:

- 907 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.