- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

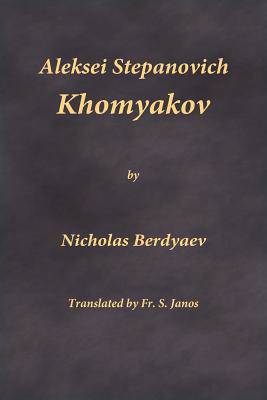

1st English Translation from Russian: "Aleksei Stepanovich Khomyakov" is an insightful book penned in 1912 by the eminent Russian religious philosopher, Nicholas Berdyaev (1874-1948). Under the perspective of "Khomyakov and us", the book explores, at depth and with extensive quotes, details of Khomyakov's life and thought. The book presents a number of ironies. A. S. Khomyakov was a central intellectual figure within the current of classical Slavophilism, which is typically glossed over for students of Russian thought as a conservative defense of the backwardness of the old Russian lifestyle; Khomyakov's view of Europe, however, as "the land of holy wonders" explodes this calumny. Rather, it is an Europe which is to be deeply engaged in accord with the Russian national psyche, not merely parroting the West. Khomyakov thus reworked Hegel and Schelling into a philosophy of "concrete idealism" based upon "an integral wholeness of life". The Slavophils supported the Russian Autocracy, but Khomyakov was regarded as a "dangerous man" by the tsar's functionaries. Khomyakov grounded Autocracy upon historical an event, when the Russian people peacefully and in accord chose Mikhail Romanov and his descendants to "assume the burden of rule". In this was a "poison pill". Khomyakov was an avid supporter of the Orthodox Church, but his theological writings were not allowed to be published, and had to be printed abroad, in French. Freedom, authentic freedom was a core tenet of the Slavophil conservatism, rendering them incompatible for employ by the bureaucracy, which they detested. Unlike the later leftist Narodniki (Populists), who were weighed down by a sense of guilt and alienation from the "narod/people", the Slavophils sensed themself at one with "the people". The Orthodox Church was central a motif in Slavophil thought. Khomyakov saw the inner essence of the Church as comprising "love and freedom". Against papal pretensions he coined the concept of Sobornost', a vision of true catholicity grounded in communality, based not upon force and blind obedience, but rather upon authentic love and freedom, as any true community must be. Khomyakov discerned within history two distinct and conflicting creative types. The Kushite type creates massive works in mute stone, in objectified and depersonalising materiality, and relates to reality in fetish magical an attitude. The Iranian (Zoroastrian Persian) is otherwise, reflecting the inward freedom and fluid plasticity of life in the human word and consciousness of "person", and is most manifest within Judaism and in Christianity. Berdyaev is critical of Khomyakov on various points: reliance upon a static and outmoded lifestyle, their apocalyptic deafness to the imperative "Thy Kingdom Come" of the "Our Father" prayer, an insensitivity to the mystical dynamics of the sacraments and mysticism in general, and a blind hostility to the religious heritage of Roman Catholicism and the Romance peoples, apart from the issue of the papacy. But there resonates strongly within Berdyaev his already existing core motifs of person, freedom, creativity, spirit, which are apparent there as well in Khomyakov's thought, in embryonic a form. All this renders Khomyakov as revolutionary in spirit under conservative a guise. A curious paradox quite ironic! This echoes in spirit also the famous saying by St Alexander Nevsky: "Not in power is God, but in truth". This is the first appearance of Berdyaev's 1912 book, "Aleksei Stepanovich Khomyakov", in an English translation. It represents yet another hitherto unavailable work within our continuing series of efforts at translation of primary texts in Russian Religious Philosophy, under the imprint of "frsj Publications".

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Vertaler(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 224

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780999197912

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/08/2018

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Gewicht:

- 303 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 90 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.