Bedankt voor het vertrouwen het afgelopen jaar! Om jou te bedanken bieden we GRATIS verzending (in België) aan op alles gedurende de hele maand januari.

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- In januari gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Bedankt voor het vertrouwen het afgelopen jaar! Om jou te bedanken bieden we GRATIS verzending (in België) aan op alles gedurende de hele maand januari.

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- In januari gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

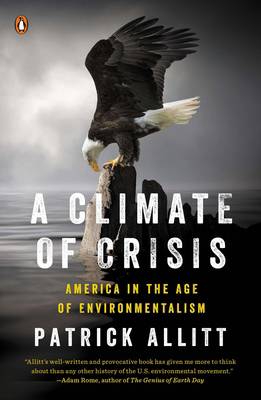

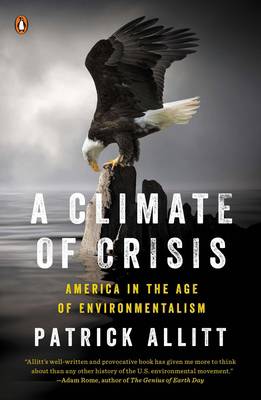

A provocative history of the environmental movement in America, showing how this rise to political and social prominence produced a culture of alarmism that has often distorted the facts Few issues today excite more passion or alarm than the specter of climate change. In A Climate of Crisis, historian Patrick Allitt shows that our present climate of crisis is far from exceptional. Indeed, the environmental debates of the last half century are defined by exaggeration and fearmongering from all sides, often at the expense of the facts. In a real sense, Allitt shows us, collective anxiety about widespread environmental danger began with the atomic bomb. As postwar suburbanization transformed the American landscape, more research and better tools for measurement began to reveal the consequences of economic success. A climate of anxiety became a climate of alarm, often at odds with reality. The sixties generation transformed environmentalism from a set of special interests into a mass movement. By the first Earth Day in 1970, journalists and politicians alike were urging major initiatives to remedy environmental harm. In fact, the work of the new Environmental Protection Agency and a series of clean air and water acts from a responsive Congress inaugurated a largely successful cleanup. Political polarization around environmental questions after 1980 had consequences that we still feel today. Since then, the general polarization of American politics has mirrored that of environmental politics, as pro-environmentalists and their critics attribute to one another the worst possible motives. Environmentalists see their critics as greedy special interest groups that show no conscience as they plunder the earth while skeptics see their adversaries as enemies of economic growth whose plans stifle initiative under an avalanche of bureaucratic regulation. There may be a germ of truth in both views, but more than a germ of falsehood too. America's worst environmental problems have proven to be manageable; the regulations and cleanups of the last sixty years have often worked, and science and technology have continued to improve industrial efficiency. Our present situation is serious, argues Allitt, but it is far from hopeless. Sweeping and provocative, A Climate of Crisis challenges our basic assumptions about the environment, no matter where we fall along the spectrum--reminding us that the answers to our most pressing questions are sometimes found in understanding the past.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 400

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780143127017

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 31/03/2015

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 137 mm x 213 mm

- Gewicht:

- 362 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 45 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.